IPv4 Address Prices & Pricing

by Lee Howard & Peter Tobey

IPv4 address pricing has followed varied paths during the past few years. On a long-term, macro level, prices have risen dramatically. On closer examination, recent trends, including relative pricing and variations in block-size costs, tell a different, less predictable story.

Publicly Available IPv4 Pricing Data

Transfers are public knowledge, published regularly by the systems’ governing bodies, the Regional Internet Registries (RIRs). However, the prices at which transfers are completed are not. So, information about IPv4 address pricing can be substantial but is nevertheless somewhat anecdotal. In 2014 IPv4.Global began publishing information about the online platform’s experience – including prices at which transfers occur on its marketplace. This transparency remains unique and – along with public sources of transfer information – allows some significant and useful analysis.

A Brief History of IPv4 Use

At the time of the internet’s early development, a device-identification and location system was instituted. The first version was created in 1973. But the first widely-used version of it, Internet Protocol version Four (IPv4), was designed by ARPA in 1981 and includes about 4.3 billion total possible unique identifying number configurations. This quantity of identifiers was deemed more than adequate. At the time of its development, the idea of many billions of internet devices in use today seemed unlikely. Of course, now there are tens of billions of connected devices and services.

As the system grew, the central authority on the numbering convention became the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA). It coordinates many of the core functions of the internet, including IP addressing, domain name management at a base level and IP resources. IANA distributed its last IPv4 addresses to the five Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) in 2011.

IPv4 Exhaustion

The phrase “IPv4 exhaustion” refers to the moment when the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) depleted its pool of available IPv4 addresses that could be assigned to RIRs and so thereafter to connected devices globally. Of course, the exhaustion of supply at the regional distributors (the RIRs) inevitably followed.

Not long thereafter APNIC (the Asia-Pacific registry) exhausted all its available IP addresses. RIPE (Europe) ran out in 2012, LACNIC in 2014 and ARIN in 2015. AFRINIC, the African registry, has nearly depleted its supply. It now offers blocks of addresses ranging from /24 (256 addresses) to /22 (1,024 addresses) only to those requesting them. Other RIRs have established waiting lists with varied wait times. Because of this, we can clearly identify one of the most obvious factors that contributes to currently high IPv4 prices: they are in unprecedented low supply.

IP Address Adoption

As mentioned, IP addresses allow communication among connected devices. Everything connected to and using the internet must have an IP connection. This includes computers, phones, servers, plus – recently – televisions and refrigerators. To distribute these identifiers, the five regional authorities (RIRs) each distribute IP addresses to IPS (lnternet Service Providers) who act as local registries. They allocate to clients.

As the number of devices has grown, and the supply via the original distribution channels evaporated, other markets arose. Holders of sometimes large quantities of addresses found themselves with unused IPs. Some estimates set the total number of unused IPs at nearly one billion. At the same time, new organizations, and those that are growing, need additional resources. The “cloud” services, large retail users and other national and international providers have created significant world-wide demand for these resources.

It should also be noted that IPv4 is a well-tested, thoroughly mastered protocol that is relatively straightforward and so easy to implement and maintain. The broadly-available skill sets needed to install and manage IPv4 addresses and the general familiarity with them has contributed to the continued use of IPv4.

The New Protocol: IPv6

In response to the pending exhaustion of IPv4 addresses, a task force (The Internet Engineering Task Force – IETF) was formed to respond. In 1995 the IETF delivered IPv6 (Internet Protocol version Six). Its configuration is vastly more expansive than IPv4 as it is built on a 128-bit address layout that permits trillions of trillions of unique addresses. However, while it was created to replace IPv4, adoption of it has been slower than anticipated. Among the challenges to IPv6 adoption is significant conversion costs, conversion and management skill levels and hardware considerations.

Some older devices simply will not operate using IPv6. Plus, the two protocols are unable to communicate with one another without an intermediary. There are solutions to this problem. But among the impacts of operating the protocols in tandem is that doing so has effectively extended the life of IPv4. So, the two are functioning today across many networks.

IPv4 Prices and The Expanding Internet

The above describes a technology environment that lives in the midst of huge information and business developments. Demand for connectivity in general, with easy, cheap and compatible connections among devices that can be deployed quickly, has grown steadily. So, the challenges of IPv6 have buoyed demand for available IPv4 addresses. Along with demand, and faced with limited supply, prices have risen.

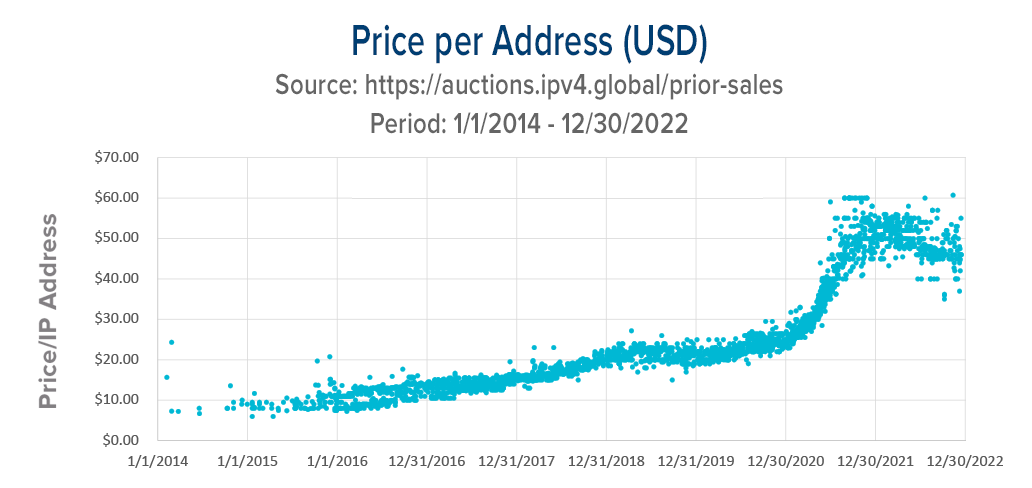

IPv4.Global pricing data.

The Last Decade

The graph shown above illustrates IPv4.Global’s online marketplace pricing experience. Information published by the site – and so made publicly available – undoubtedly contributed to the narrow band of variation between high and low costs that developed beginning in early 2016. Market information is always an influencer of pricing. The market’s clear understanding of prices for blocks of all sizes seems to have helped maintain a consistent range of unit prices for the assets. What’s more, prices rose steadily, if relatively slowly, during the following five years.

It should be noted that inflation in the US was generally low during the period 2015-20. And while, in retrospect, prices of IPv4 addresses rose gradually (in comparison to later increases) the rate of growth was nearly 20% per year. Per IP prices rose from about $10 to $25 during the period.

IPv4 prices paused their gradual rise in 2019, with various block sizes trading at a slightly wider range of prices. Then, the first half of 2020 saw many existing networks stopping their growth as the pandemic swept the world. New networks and network expansion slowed or stopped entirely and along with it much of the demand for IPv4 addresses.

IPv4 Prices – On the Rise

In early 2021 much of the vaccinated world restarted. New network builds happened and expansions resumed. This clearly produced an increase in demand for IPv4 addresses as their convenience – relative to IPv6 – prevailed.

At the same time, much of the potential supply remained on the sidelines. Renumbering projects didn’t resume quickly so supply was constrained. Many under-used blocks had been deployed using interspersed allocations of addresses, with wide and unwieldly gaps between them. Renumbering to consolidate use and so make contiguous addresses available for sale did not restart quickly. This was, in part, the case because the process can require six months. Plus, networks deploying addresses inefficiently continue to function perfectly well. So, the urgency to renumber them is not great. With demand high and supply constrained, prices rose. Very rapidly. During 2021, IPv4 prices more than doubled.

Another curious change occurred in 2021. Though pricing remained within a tight band through the first half of the year, at about $40 per address the spread widened. With very short supply, some buyers’ urgency prevailed, and prices rose even faster. Peak pricing reached $60 within months. However, given the high cost of the assets, liquidation urgency also increased: holders wanted to monetize quickly. Some of these sellers demanded maximum prices while, apparently, some were willing to sell below market to careful shoppers.

The Price Range Expands

As is evident in the price graph shown, the second half of 2021 produced wildly varied prices for most block sizes. One market essentially became several of them, with buyers’ various needs and different block sizes producing significant price differentials. The many causes of these changes remain uncertain, even though market watchers can identify sources of pricing influence, certainty as to causes can’t be known. The market is too dynamic and too large to permit that conclusive analysis.

Block Size Impacts on Pricing

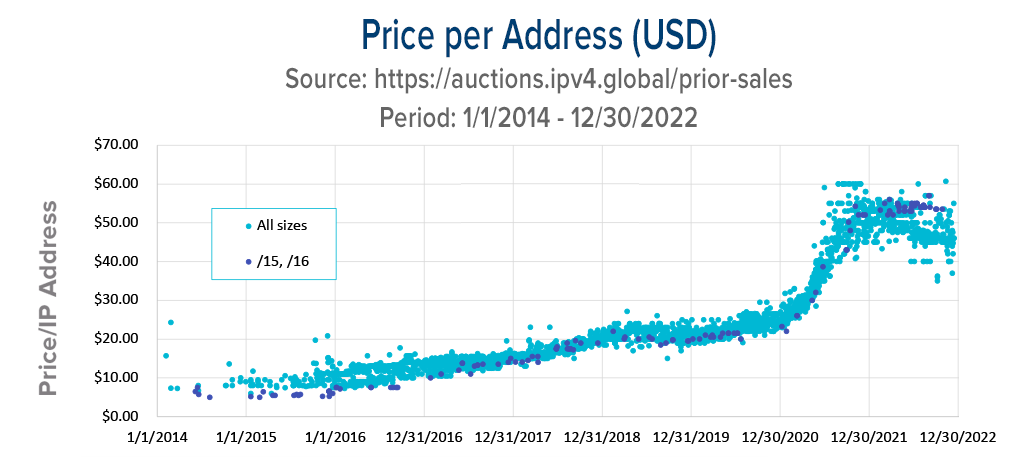

A curious price inversion has occurred in IPv4 markets. The long-term trend that discounted large blocks has reversed.

The graph below identifies /15 and /16 (large) block pricing throughout the period in the form of dark spots. It is evident that, for most of the timeframe here (2014 to the first half of 2021), large blocks sold at a significant discount.

IPv4.Global pricing data.

One might guess that the administrative chores related to large-network needs were most efficiently and cheaply satisfied with these blocks. This would, of course, increase their value. But, perhaps, this influence on pricing was overcome by the relatively high absolute cost of a large block and/or the scarcity of buyers for them. What’s more, simple price-sensitivity may have been more acute for larger purchases. Causation is tricky, here.

It is also possible that the demand for small blocks exceeded their supply, driving prices up. At least relative to the supply-demand relationship of larger blocks. Regardless of the various influences on large block prices, they remained relatively low (cheaper) throughout this period.

However, the discount for these large blocks created an unusual opportunity in a commodities market like IPv4. A large bundle of addresses was cheaper per IP address than the same block, subdivided. During 2020-2021 larger sellers and savvy traders in these assets began to break them up and sell the addresses in smaller, more costly-per-IP batches. This tactic increased the value of a large block when sub-divided.

The lower per IP price of large-block IPv4 addresses ended during 2021 as IPv4 prices began to trade in wider ranges. As that happened, the relationship between large and small block prices changed in many ways. Large blocks became (relatively) more costly than smaller ones but continue to trade in a relatively tight range. Smaller blocks began to be traded in a wider – and generally lower – range.

IPv4 Block Price Inversion

Today, sellers can expect a higher price-per-address for larger blocks. As noted, the cause of this inversion from recent history can’t be fully known. But it makes sense in terms of scarcity: we know there are more /18s than /16s. Prosperous, aggressive operations in online retail, communications and cloud-based services are growing rapidly and profitably. As a result, the urgency to accumulate IP addresses is acute and their value to operations very high.

Inversion pricing data from IPv4.Global.

Theoretically, a buyer could piece together smaller blocks and resell them as a newly-formed bigger blocks (/16 or more) for a bit of profit. However, locating and combining consecutive small blocks is very difficult. Non-contiguous, cobbled-together bundles of blocks are less desirable to bigger companies since the IP addresses that compose them are not digitally sequential and so present numbering issues.

It’s impossible to know if this inversion will continue, flatten or reverse. What’s more, the relative impacts of a slowing world economy and recession concerns have surely influenced near-term network development. The relative impact the economy and economic expectations may be having on the relative pricing of small, medium and large buyers remains unclear. As a result, the market situation is a curious one – and certainly unpredictable.

Global Trends

As noted above, one thing is undeniable: 2022 was a year of some trepidation on the part of businesses as inflation concerns raised interest rates and recession became a worry. The anticipated slowing of the economy – and especially that of the technology sector in general – caused many companies to reduce their investments.

This is the case because any networking infrastructure investment is likely to be a long-term one. Since the build-out of these investments is often extended, the benefit is delayed. All of which means the expense is current and the improved efficiency or opportunity is deferred. So, the sagging economy in connection with rising energy costs, a war and the global pandemic surely dampened investment in all infrastructure. Not surprisingly, network growth plans have (and continue to) take a hit as a result. The relative effect of this pull-back can’t be measured and its duration is unknowable.

In a nearly-pure commodities market like that for IPv4 one might expect demand to play a very significant role. However, the global economy notwithstanding, transfer volumes at both RIPE and ARIN (Europe and North America) increased significantly 2022 over 2021. Transfer records show that, worldwide, non-merger & acquisition transfers increased approximately 35% one year over the next.

Routing Table Growth

New entries to IPv4 and IPv6 routing tables indicate the overall growth of those networks worldwide. In both cases, growth slowed in 2022 significantly and at about the same rate. This slowing, considering the expanded transfer rates worldwide, is surprising. Plus, the similarity of the rate of change in the two routing tables suggests that some factor is at work other than IPv4 market decline. Put simply, IPv6 deployment rate slowing can’t be due to over-deployed networks and so shrinking markets. IPv6 is far from a saturated market and so other influences must be in effect. Because IPv4 mirrors the slowing of IPv6, one is inclined to believe they are being influenced by similar factors.

In Sum

Any summaries here are necessarily inconclusive. The influences on pricing in the IPv4 market are clearly at cross-currents with one another. Marketplaces are strong and infrastructure expansion has undoubtedly slowed, if only temporarily. How deep an economic decline may occur and how long it may last remains unknown. How and if that macro-economic impact will impact IPv4 markets is also anyone’s guess.