Understanding Network Abuse

by Leo Vegoda

Most networks distinguish between abuse of the network and abuse that is carried out over the network. Abuse of the network degrades its service in some way. Abuse carried out over the network relies on it working properly. Networks can often prevent or reduce abuse of the network itself. But abuse carried out over the network, like banking fraud, must be investigated by law enforcement.

Early Abuse

One of the first network abuse investigations focused on people who had gained access to Prince Philip’s email account in 1985. This is an example of abuse carried out over the network and was executed, according to the perpetrator, as a protest against bad security measures. The Prince’s email account, on BT’s private Prestel service, was probably unused and included only unread birthday greetings for Princess Diana. The failed prosecution under fraud law led to the Computer Misuse Act.

Another newsworthy network abuse event was the Morris Worm from 1988, named after its creator Robert Tappan Morris. This was a self-replicating program that used insecure software and the internet. It disabled the machines it infected. This is an example of abusing the network itself. Paul Graham, who went on to co-found Viaweb with Morris, claims that Morris wanted “simply to see if it could be done. If it had worked as intended, it would have been barely noticeable.” Morris was convicted under the 1986 Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

These early abuse events were carried out with youthful enthusiasm and without malice. They didn’t cause serious social damage because relatively few important services relied on computers. The consequences of abuse are higher now. Clearly, this is because the internet is a mature infrastructure relied on by business, government, and healthcare.

Kinds of Abuse

Address Hijack: Accidental

Organizations can configure any IP addresses onto their networks. In most cases, organizations only want to configure their own addresses. But typos can lead to your addresses being used on someone else’s network. When that happens, traffic intended for you might go to them. Losing traffic you want is obviously bad. But this kind of error can also cause major outages if too much traffic is sent to the wrong place.

If the issue is a mistake, the organization getting the extra traffic will want to fix things as quickly as possible. One example of this is from 2008, when Pakistan Telecom misconfigured a filter that was supposed to stop access to YouTube from inside Pakistan. Instead, much of the world’s YouTube traffic was sent to Pakistan Telecom. The flood of traffic overwhelmed Pakistan Telecom and the issue was resolved in about an hour.

Smaller networks might not notice events like these if they happen outside of normal business hours. But there are monitoring services that can alert you to this kind of hijack. Some specialized services have very low costs, while others both charge and offer more.

One way to help everyone is to filter claims about addresses based on the IRR and RPKI. Both approaches help you tell other networks which IP addresses are yours. Those networks can then reject other networks’ claims to route your IP addresses. Tools to process IRR and RPKI data are freely available and well maintained.

Address Hijack: Intentional

A more malicious kind of address hijack relates to the registration itself. In these cases, the hijacker will try to update the (official, Regional Internet Registry) registration so that they can use or sell the addresses. The approaches used by miscreants and the defenses employed by the RIRs have been evolving for 20 years.

Hijackers have previously used approaches like:

- Registering a company with the same name but in a different jurisdiction;

- Registering a similar company name in the same jurisdiction; and

- Registering an expired domain name linked to a registration.

Hijackers have refined their approaches as the RIRs have improved their due diligence checks of any new registration. As a result, this kind of attack has become harder to pull off. Nonetheless, RIRs occasionally need to revert transfers based on fraudulent documentation. Even a temporary hijack can disrupt an organization’s internet access. That could enable other kinds of attack, damaging both finances and reputation.

You can protect your addresses by regularly reviewing the information held on your organization by the RIR. Make sure that the company name and contact information are current. And make sure abuse reports are received and acted on.

Denial of Service

Pakistan Telecom noticed its misconfiguration immediately because it received so much internet traffic. The sheer volume of unexpected traffic overwhelmed their network. It was a self-inflicted Denial of Service (DoS) because they lost the ability to use their network for its intended purpose.

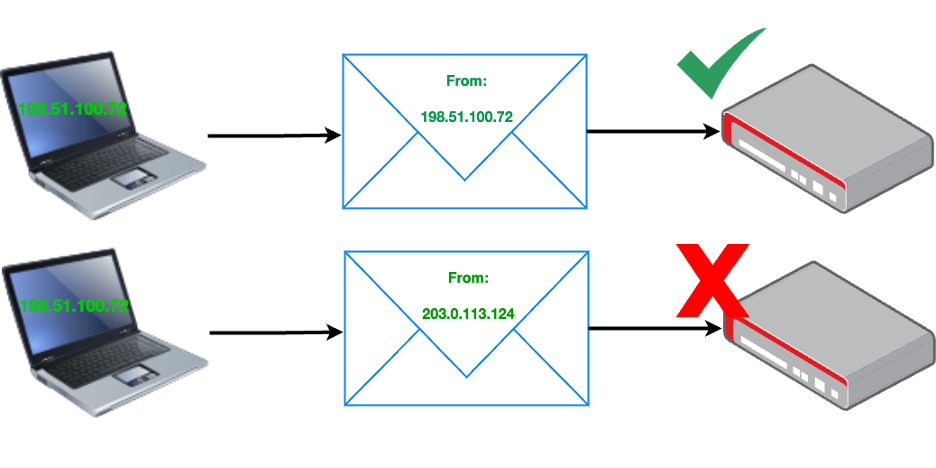

Many DoS attacks don’t come from a single source. They are known as Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks. Often these are possible because network operators have not implemented reverse path filters. These filters stop a network sending packets with a foreign – inaccurate – source address. The attack is called IP Source Address Spoofing and allows a single source to send great numbers of messages that appear to come from multiple sources.

Deploying IP source address filters has been best practice, published as BCP 38, for over 25 years.

BCP 38 filters: The router rejects the packet coming from the laptop when its origin IP address does not match the assigned address

The impact on other networks can be severe. One small packet can generate a very large response. If a malicious actor can trigger a lot of those packets to be sent using IP addresses from the victim’s network they can overwhelm it. One way they do this is with DNS, the internet’s naming system. A small query can trigger a large answer, so this is called a DNS Amplification Attack.

For instance, a single DNS query might use 64-bytes. That query could result in a response 50 times larger, sent to a victim network. Bad actors often control large networks of machines, including things like home ccTV systems. Companies that sell DDoS protection services describe under 500Mb/s as “relatively small” – and these are the overwhelming majority. But the attack only needs to be just big enough to overwhelm the victim’s network. A small fraction of attacks are between 10Gb/s and 100Gb/s.

Impacts start with poor performance in online gaming. They extend into increased costs for IP transit and DDoS protection services. Ultimately, this kind of attack can make a network unreachable.

DoS and DDoS attacks are illegal. But criminal businesses have been selling them for years. They claim that they are for ‘stress testing’ networks. Law enforcement has investigated these services. They have taken their domain names and charged the operators with crimes.

The US and other governments have also responded with new regulations to improve the security of the devices whose security has been breached. But that’s only half of the solution. Why don’t networks deploy BCP 38 filters, though?

One possible reason is that the organization bearing the costs doesn’t get the benefits. The service provider networks charge based on usage. DDoS traffic carried over their network gets counted when calculating invoices.

Another is that some network operators use older equipment in places where filtering is needed. Many networks continue to use older equipment as long as possible. They want to avoid the capital cost and operational disruption of replacing equipment. Older equipment will struggle to apply filters for large amounts of traffic.

The industry has developed a program to address this. MANRS, the Mutually Agreed Norms for Routing Security, is an initiative to encourage security improvements. It requires participating networks to deploy BCP 38 filters. But there are under 1,000 members of the MANRS Networks program and tens of thousands of networks on the internet.

DNS Data

DNS can be abused in other ways. Two of the most prominent are changes to DNS answers, often called DNS lies. DNS lies can send innocent users, and lots of traffic, to the wrong place.

One method of attack is to change the answers given by the authoritative server. This disrupts the network by sending traffic to the wrong place. It is hard to do as it requires significant access to the target’s network. Standard monitoring tools should detect this kind of attack.

Another approach is to poison the answers in the DNS resolvers that get DNS answers for users on a network. This is called cache poisoning, or the Kaminsky attack, named after security researcher Dan Kaminsky. It is harder for domain owners to detect as only a small fraction of users will get the DNS lie.

One protection against DNS lies is DNSSEC. This relies on the operator of the DNS zone signing their answers with a digital certificate. Users, or the DNS resolver they rely on, must then validate those answers. With DNSSEC in place, a DNS lie is obvious and can be rejected.

ICANN requires gTLDs, like .com or .org to be signed with DNSSEC. ccTLDs, like .fr and .uk, set their own policies. Only two-thirds have chosen to sign so far. The Internet Society measures just a third of resolvers or users validating the signatures. That’s probably because under six percent of .com domains are signed with DNSSEC.

Another reason that most DNS resolvers don’t validate DNSSEC is the complaints they get when the signer makes a mistake. One example is when NASA broke its own DNSSEC configuration. Comcast, a large ISP, was validating DNSSEC and that meant its users couldn’t find NASA’s network. Comcast users were angry.

Securing domains and DNS is clearly hard, detailed work. It’s important to get things right from the registrar to the resolver. One way to do that is to outsource it to a specialist brand protection domain registrar. Companies like these specialize in protecting brands and their intellectual property.

If you’d like to validate DNSSEC to add some extra security to your own system, you can run DNSSEC-Trigger on most operating systems. You cannot run it on phones or tablets.

Hosting illegal content

While the law varies between jurisdictions, most agree on a core of what is illegal. ‘Bulletproof hosting’ companies outside these rules, and host content that legitimate businesses won’t touch. Their description comes from the idea these hosts are immune from criticism and control because they operate outside stringent laws controlling their use and content.

Specifically, they host:

- Copyrighted content;

- Illegal pornography;

- Hate speech; and

- Botnet command and control servers.

Botnets are groups of internet-connected devices whose security has been breached. This puts the device in the control of a third-party. Botnets are widely used for DDoS attacks and sending spam. Botnet controllers tell the compromised devices what to do.

Bulletproof hosters tend to operate outside of rule of law jurisdictions. For instance, the Russian Business Network is based in St Petersburg, Russia. One way they keep content available is by placing it on otherwise legitimate websites they have hacked. The content is not linked to from the hosting website, only the illegal website.

This increases cost for the actual hoster and might add some legal risk if they are held responsible for serving up illegal content.

One way to keep your users safe from bulletproof hosters is to filter based on a reliable reputation list. One example is the Spamhaus DROP list. It’s freely available to everyone as a public service.

Spam

Unsolicited Commercial Email (UCE) is often called spam. The first unsolicited commercial advertisement is thought to have been sent to over 5,000 Usenet discussion groups. It advertised Green Card lottery services. Laurence Canter claims the spam brought in between $100,000 and $200,000 in 1994 at almost no cost to him and his partner.

UCE can both overwhelm mail services and fill up people’s mailboxes. Both network operators and users hate it because the low cost of sending means there’s no incentive to carefully target offers to appropriate prospects.

Most mail and access contracts now forbid sending spam. In contrast, the large mail providers have reciprocal relationships with email marketing services. The key change since the early 1990s is the opportunity to reliably unsubscribe from email marketing messages.

Message with prominent unsubscribe link.

The key objections to spam in the 1990s and early 2000s were abuse of resources and the inability to unsubscribe. Laws like the CAN-SPAM Act and GDPR, and the professionalization of internet marketing, have changed things. People can now choose to sign up for email marketing knowing that unsubscribe requests will be honored.

If you need to send marketing messages or transactional email, find a company that will help you obey the laws relevant to your business. If you are worried about too much incoming spam, find a reputation list that works for you.

Take Control

Most networks have a person or team responsible for responding to abuse issues. Whether caused by their users or affecting their network they must be addressed. The RIPE NCC runs and publishes free webinars on setting up an Abuse Desk. This webinar is a good free introduction to this subject.

Many network operators have an Incident Response Team. They centralize responsibility for preventing, detecting, and resolving security incidents. Incident Response Teams share experience through FIRST, the Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams.