Use Peering to Lower Network Costs

by Leo Vegoda

For organizations with lots of client and server computing devices, taking control of their own internet connectivity can bring advantages. It can lower costs and improve performance. In particular, peering can improve connectivity to other local networks, including content networks with a local presence. But what does ‘taking control’ really mean?

It’s a bit like office space. Some organizations choose fully managed offices and others buy or rent space, managing some or all of it themselves. Buying internet connectivity – known as transit – is the fully managed option. Peering means taking responsibility for managing some of your organization’s internet connectivity.

In general, a transit provider will come to your location and give you full internet access. They can provide everything with just one contractual relationship. In contrast, peering is likely to mean paying for a circuit to a data center hosting an Internet Exchange Point (IXP) and then paying to connect to the IXP. You’ll need to manage multiple relationships, contracts, and some extra equipment.

You can mix and match. It is common to peer with other local networks and some content providers, while buying transit to get access to distant networks.

Peering has two meanings. From a business perspective, peering networks connect as equals. They trade access to each other’s downstream customers without charge. In contrast, transit is a commercial arrangement for internet access. In BGP, the network protocol that connects internet networks, neighboring networks are called peers. So, in a technical sense a BGP peer can be an upstream transit network.

But the internet is constantly changing, so that connectivity needs to be managed. If internet connectivity is a convenience but not essential, you probably don’t need to peer. But if you need to improve uptime, performance, or manage costs, peering could be one way to achieve your goals.

Almost all organizations continue to buy some transit because peering is used to access nearby networks. As most networks are based in a city, country, or continent, they will need to buy transit to reach the rest of the world. Only a handful of global internet networks do not buy transit. That’s because these very large networks peer with other very large networks. They sell services but don’t buy them. Lumen is one example – CAIDA ranks them as having the most reach at the time of writing. Sometimes, these networks call themselves Tier 1 networks.

Why Peer?

Networks peer to reduce latency, improve resilience, and manage cost.

Latency is the time it takes for a data packet to get from sender to receiver. For instance, data from London should get to Amsterdam in under 10ms. But the same data would take about 80ms to get from London to Boston.

Directly connecting to local networks can improve the experience for users by shortening the path data takes. This is important for highly interactive services like gaming, VoIP and video conferencing. They need low latency connections to avoid poor user experience from data taking a longer route than needed. They try to peer with many networks to keep traffic local.

Resilience is the ability to continue offering a service when a part of the network fails. This is both important during scheduled maintenance windows and when fibers or other equipment fail.

Peering can improve resilience. There can be multiple routes between any two places on the internet. One might be preferred because it is cheaper or shorter. But having multiple internet routes is no different from being able to choose between multiple airlines when flying to another city. Any single link, like a transit connection, can go down. But with multiple connections, a network can retain significant connectivity.

For instance, a network buying transit from an upstream in the NIKHEF data center in Amsterdam could also peer at multiple IXPs based there. When a transit link goes down for planned maintenance, they could connect to hundreds of networks through AMS-IX and dozens through Asteroid.

This can be important for networks whose users need to exchange data locally. For instance, local businesses, banks, and other financial services networks might need to peer to eliminate a single point of failure at a transit provider.

The cost of peering can vary but it is often cheaper than buying transit when your organization has its own IT team. This is partly because you are taking on responsibilities like buying network equipment and placing it in data centers to peer with other networks.

Where to Peer?

An IXP is a physical infrastructure for exchanging internet traffic between three or more networks. Three is the minimum number because two is just a point-to-point link.

IXPs are based in data centers, also known as interconnection facilities. Some IXPs are distributed across several data centers in the city they serve. Some IXPs are run by the data centers themselves as an added value service for customer networks.

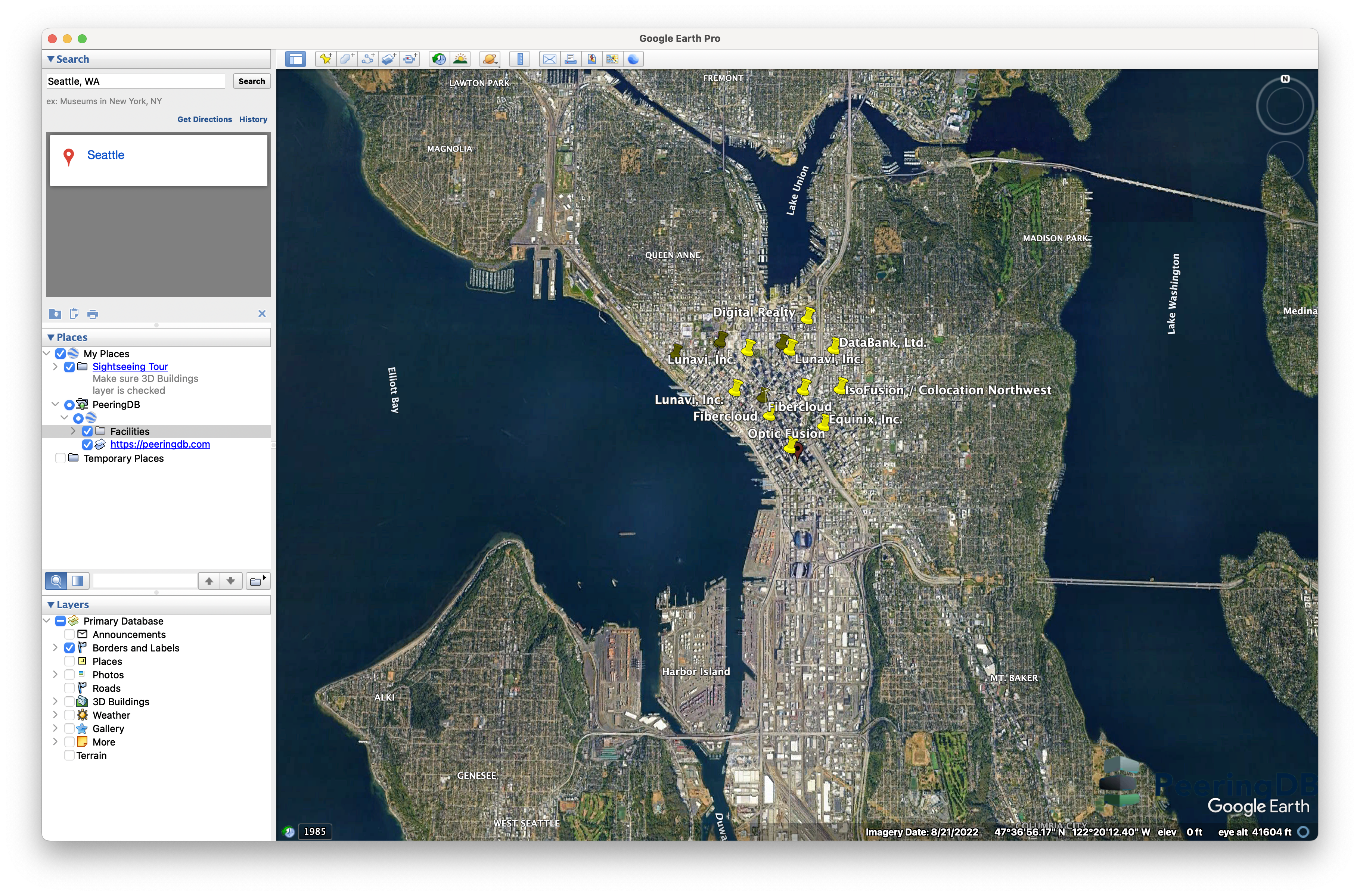

PeeringDB data for Seattle, WA shown in Google Earth Pro from its daily KMZ dataset.

This means that connecting networks can make a single connection to the IXP and have access to many networks. The alternative would be to connect to each of the other networks separately. That requires a lot of configuration and constant maintenance as networks move around.

IXPs have made the configuration requirements for peering very simple through their route servers. This multilateral peering lets networks peer with the routeserver and so get access to all the peering networks’ routes with a single configuration entry.

Of course, it is possible to make multiple connections to the IXP and to use it to peer directly – bilateral peering – with another network as well as getting their routes via the route server.

Some IXPs include some rack space in their membership fees. Others don’t charge at all because they are volunteer projects. The wide variety in pricing and business models reflects history and development models. Some IXPs grew as neutral, non-profit organizations in the 1990s, others offer an internal IXP as an added value offer for a data center. Sometimes, people create an IXP to keep traffic local and encourage economic and network growth in that community.

The key price is for a port – connection – on the peering LAN. In 2021, Euro-IX, the European organization for IXPs, published a report showing an average price of €485 per month for a 1 Gb/s port. Port prices go down, so 2024’s average price is likely to be lower.

Finding IXPs and Networks, Learning More

There are multiple databases supporting interconnection. Two of the main databases are PeeringDB and IXPDB. PeeringDB’s database focuses on user supplied data while IXPDB gets its data from IXPs. PeeringDB, in contrast, lets connecting networks decide what information they want to share. That means, they can choose to have the IXPs they connect to contribute technical configuration about them, like the IP addresses they use to connect to the peering LAN.

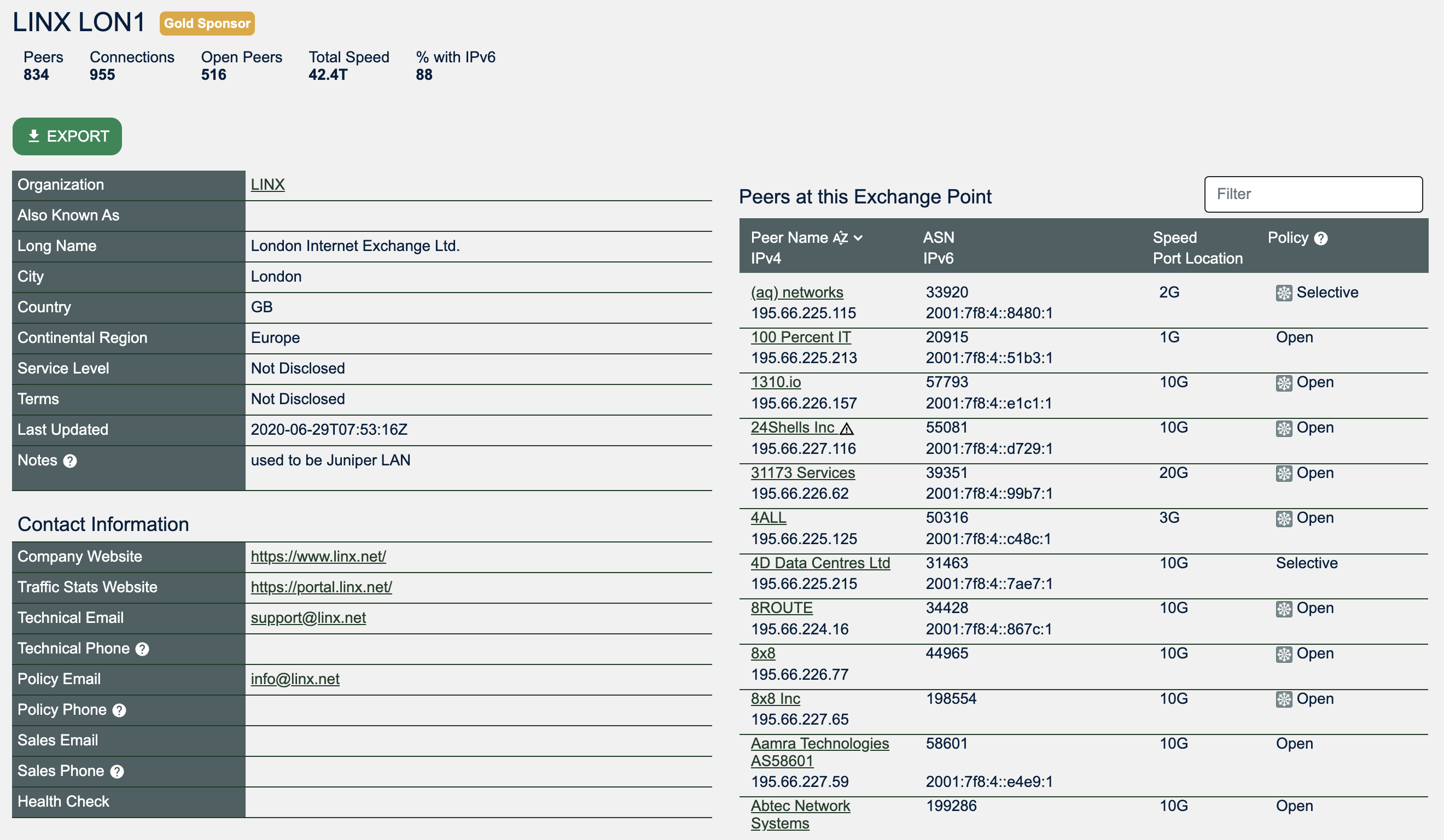

LINX’s PeeringDB entry shows the IP address and ASN of connecting networks

Both support publication of data in a JSON file, generated by the IXP, that can be used to automate configuration.

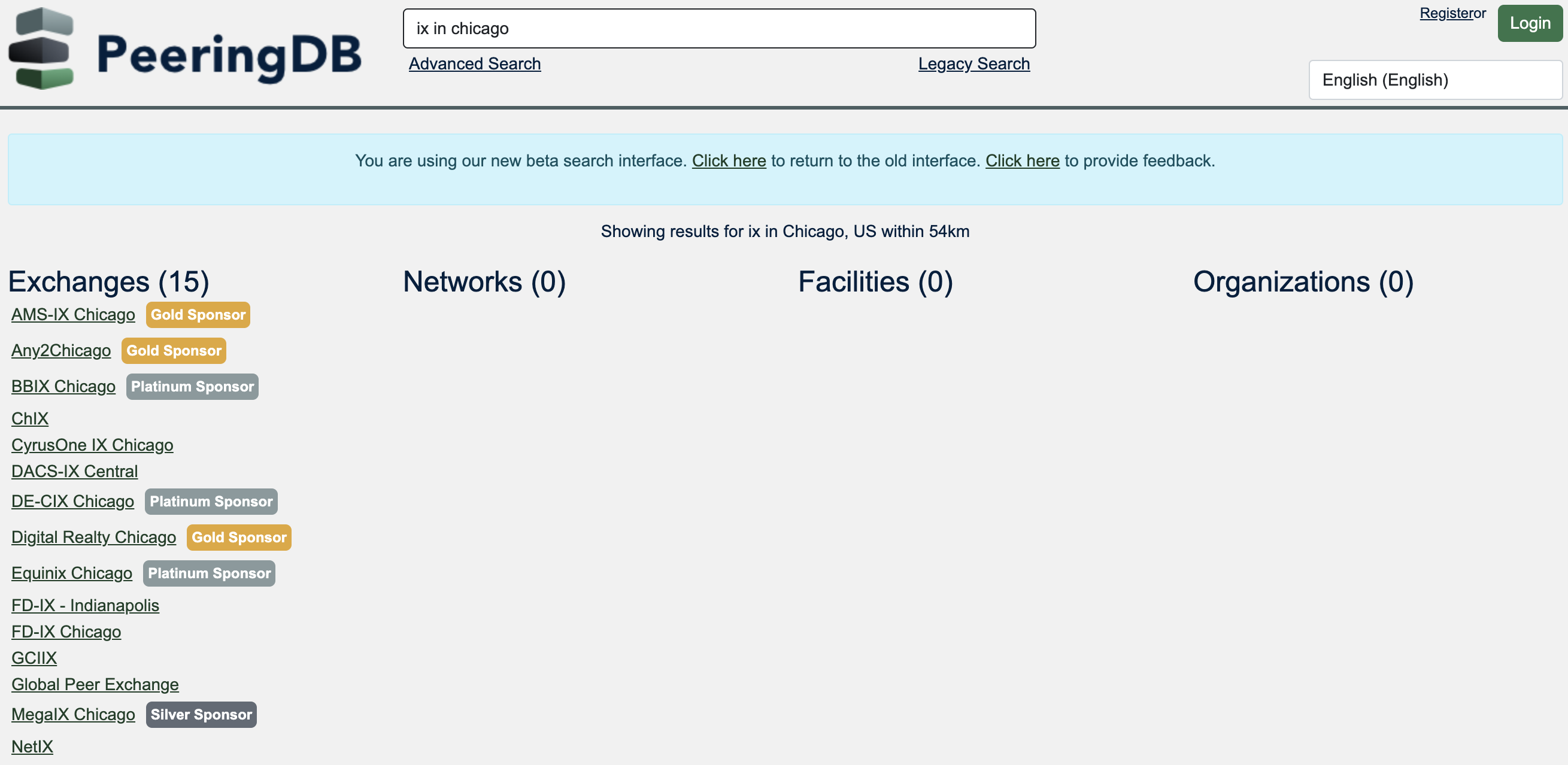

PeeringDB’s website makes it easy to find IXPs, networks, carriers, and more.

Some networks arrange bilateral peering and private network interconnects, often called PNIs, over mail. Others, like Google, have peering websites. Some, like Cloudflare and Meta, will require you to authenticate using your PeeringDB account. This is because they want to get configuration information from PeeringDB.

Peering with Cloudflare requires authentication with your PeeringDB account

Learn More

Euro-IX has developed the Peering Toolbox, a free online training course for networks that want to learn more about BGP and peering. It explains a lot of what you need to do and how to do it but doesn’t discuss tools for managing peering relationships.

One option worth looking at is 6Connect’s ProVision platform. It automates complicated network provisioning workflows and contains a Peering Manager for one-click configuration. It takes the technical challenge out of peering and simplifies network management.